Sustainable cities? We're not there yet

More people today live in cities than in rural areas … a first in human history. The question is: is this a good thing or a bad thing for sustainability?

More people today live in cities than in rural areas … a first in human history. The question is: is this a good thing or a bad thing for sustainability?

Past studies have suggested that compact urban living is more efficient, with a lower overall environmental footprint, than country living.

At the same time, though, cities produce most of the world’s carbon emissions. And recent research has found that populous, urbanized areas can’t really be considered “sustainable” unless they also take into account the indirect impacts they have through the goods and services they import from other regions.

Meeting the food and fiber needs of the Netherlands, for instance, requires an expanse of rural and agricultural land that’s four times larger than the country itself, a Dutch study found. Other urban regions are likely to have similar beyond-border impacts.

“With currently over half the world’s population, cities are supported by resources originating from primarily rural regions often located around the world far distant from the urban loci of use,” write the authors of a recent report published in the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences journal Ambio. “The sustainability of a city can no longer be considered in isolation from the sustainability of human and natural resources it uses from proximal or distant regions, or the combined resource use and impacts of cities globally.”

“On this kind of trajectory, more than 15,000 football fields (FIFA accredited) will become urban every day during the first three decades of the 21st century,” said Karen Seto, a co-author of the study and an expert in urbanization at Yale University. “In other words, humankind is expected to build more urban areas during the first thirty years of this century than all of history combined.”

And humans are filling those expanding urban areas at the rate of 185,000 new city dwellers every day.

Managing such large and rapidly growing cities in a sustainable way will mean gaining a better – and, preferably, real-time or near-real-time – understanding of myriad complex factors like resource flows and carbon emissions. Fortunately, noted lead author Sybil Seitzinger, executive director of the Stockholm-based International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, “digital technologies are now putting this kind of information within our grasp.”

For example, more advanced, data-driven insights could help decision-makers plan for city population growth with less nature-damaging sprawl. Without better planning, the total land footprint of cities by 2030 could be three times what it was in 2000, another study co-authored by Seto found. That could cause massive losses in biodiversity and vegetation, with all sorts of potentially negative knock-on effects.

Among the organizations that have been working to steer cities toward greater sustainability are the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group and the World Mayors Council on Climate Change, as well as multinational companies like IBM, Cisco, Philips, Siemens, Accenture and Capgemini.

IBM’s Intelligent Operations Center for Smarter Cities, for example, is an IT system that brings together city data from multiple sources – utility operations, emergency services, traffic systems and more – to help managers better understand what issues need attention and where resources are most needed. And Cisco is working with a number of other organizations to update the Dutch city of Eindhoven’s information and communications technologies to deliver Virtual Citizen Services.

With so many different efforts under way to make cities “smarter,” though, there hasn’t yet been any way to measure just how “smart” a city is. The City Protocol Society, launched in late 2012 at the Smart City Expo World Congress in Barcelona, is aimed at changing that.

Described as a sort-of LEED program for cities, the City Protocol Society is working to create standards for sustainable cities and enable better sharing of information and testing of programs and technologies around the world. As its website puts it, the society’s goal is to “accelerate sustainable transformation, by offering curated guidance and collaborative action so that cities do not have to navigate their transformation journeys alone.”

Among the society’s members so far are many of the companies named previously, along with academic institutions like MIT, the London School of Economics, the Universidad de Cantabria, Younsei University and the Universitat de Girona.

Cities that have signed so far include Amsterdam, Barcelona, Bristol, Buenos Aires, Copenhagen, Dublin, Helsinki, Hyderabad, Istanbul, Lima, Medellín, Maputo, Moscow, New York, Nairobi, Paris, Quito, Rome, Seoul, San Francisco, Stockholm, Taipei and Yokohama.

While the City Protocol (CP) Society hasn’t agreed on its standards yet, it has outlined its basic mission:

“The starting point for CP is that every city has its own individual story of how it has got to where it is today. Every city faces its own particular mix of opportunities and threats and its own set of strengths and weaknesses.

“Because of this, no city can simply copy any other city’s path into the future.

“However, all cities do have some things in common with some other cities. The difficulty is how to identify those commonalities clearly enough to allow cities to decide whom to partner with, so that shared problems can be tackled together.”

‘Sustainable’ cities that might not be

It’s telling that, for as many lists as there are for “green cities,” “sustainable cities,” and “smart cities,” there’s yet no consistent, reliable, data-based – as opposed to anecdotal – way to measure and compare city performance in things like carbon emissions, low-carbon transport and resource efficiency. That could soon change, though.

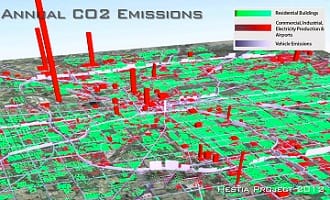

Researchers at Arizona State University, for example, have recently developed software that can estimate local carbon emissions down to the level of roads and individual buildings. They’ve so far used the system – named “Hestia” after the Greek goddess of the hearth and home – to generate an emissions map for the city of Indianapolis, and are working on similar maps for Phoenix and Los Angeles.

Other measures – say, number of cars per capita in city, which can indicate transport efficiency – aren’t yet as easily teased out on a global basis as, for example, broader metrics like cars per capita by country. And when they are available, they sometimes indicate that urban areas with a reputation for sustainability might not be as green as thought.

Consider the Brazilian city of Curitiba, which has long been held up as an example of smart, efficient transport. The city’s fast-growing population and changes in leadership policies, however, have revealed cracks in the façade. In fact, Curitiba now has more cars per capita – 1.4 – than any other city in Brazil.

If transforming an existing mega-city into an efficient, sustainable one is challenging, building one from scratch can be even more problematic. Cities have historically grown organically, in places and in ways that meet a variety of human needs, not all of them measurable. Besides, how truly “low-impact” is it to build a community for thousands upon thousands of people where one previously didn’t exist?

It’s issues like these that lead commentators like Richard Sennett – a professor of sociology at the London School of Economics and professor of social science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – to question whether planned smart cities like Songdo in South Korea or Masdar City in Abu Dhabi are the way to go.

“A great deal of research during the last decade, in cities as different as Mumbai and Chicago, suggests that once basic services are in place people don’t value efficiency above all; they want quality of life,” Sennett wrote in a recent column in The Guardian. “A hand-held GPS device won’t, for instance, provide a sense of community. More, the prospect of an orderly city has not been a lure for voluntary migration, neither to European cities in the past nor today to the sprawling cities of South America and Asia. If they have a choice, people want a more open, indeterminate city in which to make their way; this is how they can come to take ownership over their lives.”